Education

Can educational interventions raise IQ[tk]? How much of the variation in people’s IQs or general cognitive ability is the direct result of differences in schooling? Among intelligence researchers, there is an emerging consensus that schools and teachers do not have as much effect on the development of intelligence as might be expected. But first, a little history on perhaps the most earnest attempts to permanently raise intelligence.

One aspect of the emerging war on poverty in the early 1960s was aimed at the longstanding concern that poor children, especially from some minority groups, on average tended to score lower on cognitive tests, including IQ tests. At the time, the consensus among most educators, psychologists, and policy makers was that any cognitive gaps revealed by tests, especially for intelligence, were due mostly or entirely to educational disadvantages and therefore could be eliminated if poor children got the same early educational opportunities that middle- and upper-class families routinely provided. The solution for eliminating any cognitive gaps seemed obvious and the idea of compensatory education resulted in the federally funded Head Start Program. Prior to Head Start, several different compensatory education demonstration projects had been implemented on a limited basis. The Harvard Educational Review asked Arthur Jensen, a noted educational psychologist, to review the claims of these early compensatory efforts (Head Start had not yet been implemented long enough to be included in this review). Jensen’s article1 (1969) was entitled, "How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement?" He began the article with this famous sentence: “Compensatory education has been tried and apparently it has failed.” Jensen continued with over 100 pages of detailed analysis of intelligence research that revealed little if any lasting effect of the early compensatory efforts on either IQ scores or school achievement. He concluded that the empirical evidence for any major environmental effects on intelligence in general, and especially for the g factor, was actually quite weak. He concluded, “The techniques of raising intelligence per se in the sense of g, probably lie more in the province of the biological sciences than in psychology and education.” (p. 108)1 The weight of evidence from modern studies of intensive compensatory education, now rebranded as early childhood education, still fail to find lasting effects on IQ scores, and even shortlived increases are not clearly related to the g factor2. However, note that the debate over Head Start is more nuanced—a variety of behaviors may arguably be improved by the programs, such as study habits, time management, cooperative work skills, and parental support.

Ultimately, with respect to both a genetic basis for intelligence[tk] and the failure of early education to boost IQ, it is fair to say that Jensen’s hypotheses have not yet been refuted by another 50 years of new data. A revisiting3 (2012) of Jensen's 1969 report wrote the following:

Though Jensen’s presentation and the ensuing controversy were focused on the US, the issues involved were and still are clearly relevant throughout the world. ... The evidence he presented stands to this day and has not been substantively refuted.

Early Interventions

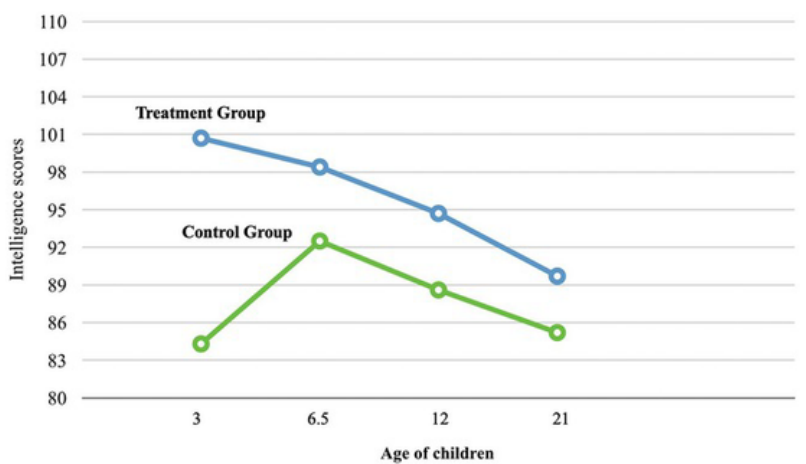

Possibly the most intensive program, the ABCDerian project (started in 1972), was aimed at a deeply impoverished group of children in North Carolina. This study4 reported positive results, compared to a control group, at age twenty-one. Because this is generally conceded to be one of the most effective (and expensive) of the preschool programs, it is worth looking at the study in more detail. The participants were children from low-SES families in North Carolina. All the children were of African ancestry. Slightly more than 100 children were assigned to the special program or to a control group. The intervention began at an average age of 4.4 months and continued until the children entered kindergarten. Depending on the period, there was one instructor for every three to six children. In addition to instruction and supervision, a nutritional program was developed and offered to both the experimental and control groups. The preschool lasted virtually the entire day, five days a week, until age five years. Participants were followed until they were twenty-one years old. The experimental group also received home visits, and parents were taught how to help their children in school. When the program ended at age five to six, the children took the Wechsler Preschool Intelligence (WIPSI) test. The experimental group had a mean IQ of 100 and the control group a mean IQ of 94. The graph below shows this and the results of subsequent testing. There are two striking features in this graph: both groups showed a steady decline in test scores over the years after leaving the project; at the same time, the experimental group maintained a roughly 5 IQ point advantage over the control group throughout. This increase is encouraging, but most intervention programs are not as intensive and show little if any increase.

Mean IQ scores obtained by the participants in the ABCDerian preschool project (N = ~50) and in a randomly chosen control group (N = ~50). The intervention ended when the children entered school at ages five to six, and they were followed until age twenty-one. Data are from Campbell et al. (2001, table 1)4.

The decline shown above is not surprising. IQ tests for children under the age of five have limited reliability and are only moderately predictive of scores at a later age. This could be because the tests for very young children are tests of cognitive functions different from those evaluated by later tests, or it could be because the cognitive systems important for test performance (such as working memory) are only slightly developed in young children. Maturing of the cognitive system likely affects test performance differences. Moreover, recent studies indicate that preschool interventions produce smaller differences between preschoolers and non-preschoolers in the twenty-first century than they did in the early research on the topic. This may indicate that the home environment of non-preschoolers has improved, which means that there is less that modern preschool can do to improve a child’s outcomes. Thus, the Abecedarian Project may be misleading for a typical, modern setting.

The Fade-out Effect

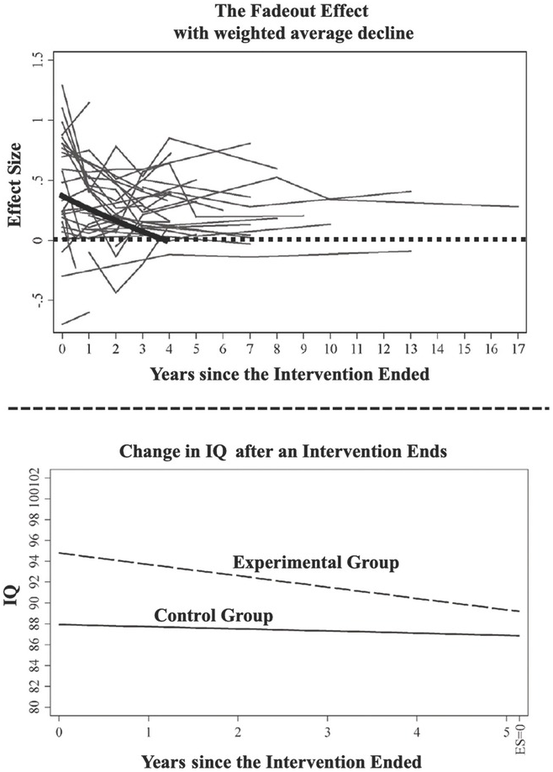

A comprehensive meta-analysis5 based on 7,585 individuals from nearly forty randomized controlled trials revealed that (1) interventions are successful for raising intelligence, but (2) the observed positive effect fades away gradually once the intervention is terminated. The meta-analysis considered any type of intervention: training studies, educational, nutritional, and so on. As depicted in below, interventions increased intelligence about 5.5 IQ points. Interestingly, (1) interventions starting at early ages did not show greater impact and (2) intervention time was unrelated to the observed fade-out effect. Perhaps the crucial message from this meta-analysis is that it may be unrealistic to expect long-lasting effects from limited interventions. Enhancing intelligence is a complex challenge that is likely beyond any relatively simple intervention.

Fade-out effect assessed by meta-analysis. (top) Effect sizes over time in different studies after an intervention has ended. (bottom) Average IQ changes decline to zero in all interventions. From Protzko (2015)5.

Although IQ scores may not increase appreciably in the long run, the picture for some aspects of academic achievement is more encouraging. One meta-analysis indicated that 80 percent of the children who participated in intensive programs had a higher level of school performance than did the median participant in the control group five years or more after the intervention ended. Participants also experienced fewer social and behavioral problems. Entry to college was also higher in participants of these programs compared to control groups6. Thus, educators would probably do better to concern themselves with teaching basic skills directly than with attempting to boost overall cognitive development. By the same token, they should deemphasize IQ tests as a means of assessing gains, and use mainly direct tests of the skills the instructional program is intended to inculcate.

Coaching

The effects of coaching in general, and the specific methods proposed in books on "how to raise your child’s IQ" can affect performance on specific tests. For a child who has been trained in such a way, the resulting test scores tend to lose a significant portion of their g loading. In other words, the scores become less reflective of the child's actual general intelligence than they would be in the absence of such preparation. One may improve the test result, but this should not be mistaken for a genuine increase in intelligence. The situation is analogous to placing a cold object in one’s mouth before having their temperature measured. The reading may be artificially lowered, but it does not change the underlying physiological state. And if the measurement is taken by a method that cannot be manipulated, the attempt to deceive is rendered ineffective. Likewise, attempting to manipulate IQ scores through test-specific training does not alter the trait the test is designed to measure.

Extreme Environmental Deprivation

The notion that the common social class differences in environment vary along a continuum of deprivation, with the environment becoming more “deprived” as we move from upper to lower SES, is a serious misconception. The environment of every SES level affords much more cognitive stimulation and opportunity for acquiring information (but not always the same content of information) than any child can fully utilize. It is an exceedingly rare occurrence when a child is found in an environment that provides too little cognitive stimulation and experience to promote normal mental growth. Such children, fortunately rare, have been reared under grossly abnormal conditions of social isolation, usually with little or no exposure to normal speech, and even with a restricted opportunity for normal experience of the physical environment.

One well-known case is that of Isabelle, an illegitimate child kept hidden in an attic with her deaf-mute mother until the age of six and a half. She had been isolated from all human contact aside from her mother and communicated only through gestures. Upon discovery, she was nonverbal, emitted croaking sounds, and behaved in a fearful, hostile, and infantile manner. Her social age was estimated at 2 years 6 months, and her Stanford-Binet score indicated a mental age of 1 year 7 months, or an IQ of approximately 25. Following her rescue, Isabelle was placed in a normal environment and received specialized instruction. Initial progress was slow, but within weeks she began to improve rapidly, progressing through early developmental stages at nearly three times the normal rate. She began speaking after two months, and within nine months was reading, writing, and performing basic arithmetic. Seven months later her vocabulary exceeded 2,000 words. In two years, her mental age increased from below 2 to about 8. She appeared then as a bright, cheerful, energetic girl who spoke well and performed normally in school. Berkeley sociologist Kingsley Davis, who studied Isabelle and last saw her in her senior year in high school, reported then that she seemed to be a completely normal teenager. Professor Davis compared her rapid early progress to the accelerated weight gain of a child recovering from illness—initially rapid until normal levels are restored, then stabilizing. While it remains uncertain whether her IQ could have been higher without the early deprivation, the most important thing demonstrated by the case of Isabelle is that extraordinarily severe deprivation throughout the first six years of her life did not have an irreversible effect on her eventual mental development and did not prevent the attainment of normal intellectual functioning.

Formal Education

Upward of 50 percent of citizens in middle- and high-income nations receive some form of postsecondary education. What impact is had on their performance on standardized intelligence tests as a result of all their intellectual engagement and academic enrichment? Does education in general have an effect on any aspect of intelligence?

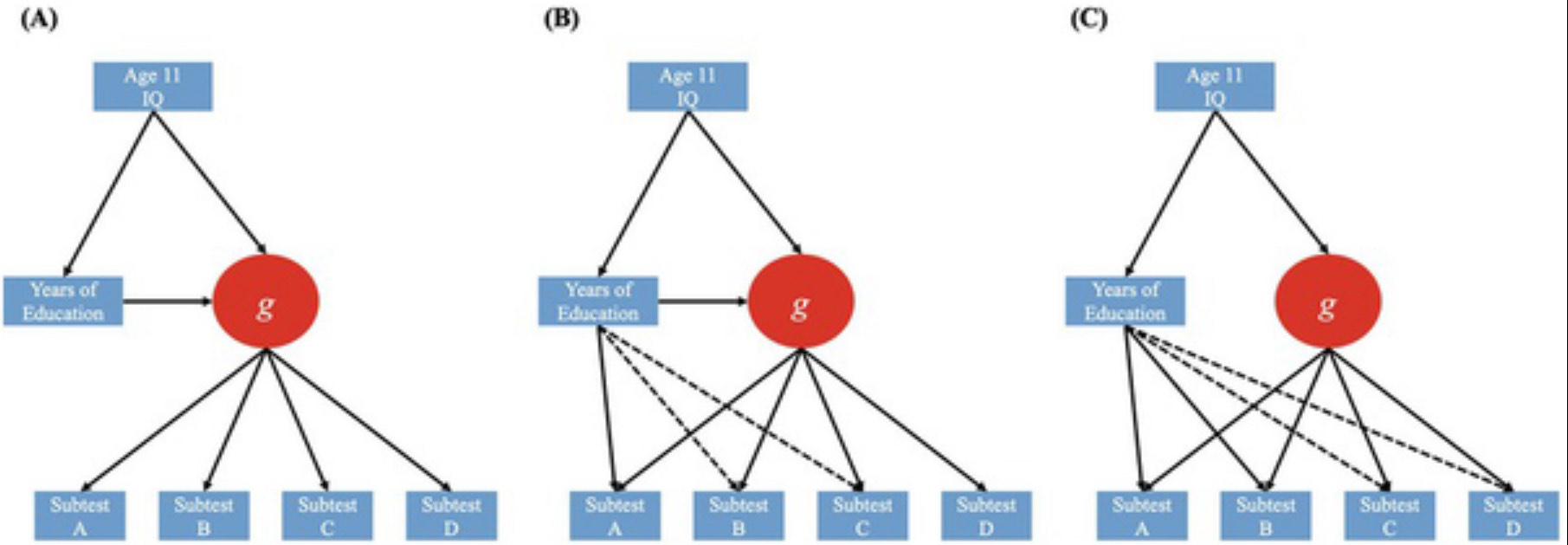

Mental abilities are hierarchically organized in psychometric models from specific abilities to broad factors to the g factor. A longitudinal study7 was designed to address the question “Is education associated with improvements in general cognitive ability (g) or in specific abilities and skills?” These researchers analyzed a sample of 1,091 individuals from the Scottish [tk, longevity study] study whose intelligence levels were measured at eleven years of age (with the Moray House Test) and tested again at age seventy with a battery of intelligence tests comprising ten subtests tapping various cognitive abilities. The models tested are depicted below. Each model predicts test performance at age seventy from test scores at age eleven.

Predicting effects of education on intelligence. (left) Model A: education (years) directly impacts g, and this influences the specific ability measures (subtests). (middle) Model B: in addition to the impact on g, there is also a direct impact of education on the subtests. (right) Model C: education does not impact g, but there is an impact of education on the subtests. Spoiler: Model C showed better statistical fit to the data than models A and B. From Ritchie et al. (2015)7.

It is reasonable to predict that individuals with higher childhood intelligence will remain within the educational setting for a longer period of time. If this is the case, then educational duration will not show any impact on intelligence. Alternatively, education might enhance intelligence through the acquisition of the cognitive tools required for the efficient resolution of the more complex items included on the standardized intelligence test batteries. Not unexpectedly, the findings showed the following:

- Intelligence at age eleven correlated with years of education (r = 0.42). The higher the intelligence at eleven years of age was, the longer the time was within the educational system.

- Factor analyses supported the presence of a single general factor (g) derived from the intelligence subtests at seventy years of age.

The main finding was that model C, with no path from education to g, showed better statistical fit to the data than models A and B. This suggests that education improves specific abilities rather than g, reinforcing that g is largely impervious to formal education. This might help explain the lack of transfer effects endemic in the educational settings8.

A comprehensive 2018 meta-analysis 9 helps answer a key question: do increases in educational duration after early childhood have beneficial causal impact on later intellectual abilities? This included more than 616,000 individuals from forty-two independent data sets. The average effect size of one year of education was 3.4 IQ points, but this was not shown to be cumulative, nor was it shown to be a g effect because required data were unavailable (a battery of tests was not used for most studies, so g could not be extracted as a latent variable). The true effect of higher-education on IQ is likely nonlinear. It might offer some marginal increase in the first few years of school, but after that, it might not offer any more.

Whether these gains in test scores attributed to education have any practical benefit remains to be determined. Changes in IQ scores of 4 points or less could be due to measurement error inherent in the test, especially in children, and fluctuations in IQ scores are not evidence of changes in g [tk]. Some components of an IQ score may be more sensitive to environmental changes, whereas the g factor might be less malleable, although this is unresolved by the weight of evidence so far.

Teachers and Students

Over the past five decades in developed countries, extensive research has consistently shown that less than 10% of variation in student academic achievement can be attributed to schools and teachers, while 90% or more is explained by factors intrinsic to students, most notably intelligence10. Even in large-scale studies using value-added models that adjust for prior student achievement, teachers account for only 1–7% of the total variance in outcomes at all educational levels. In contrast, the primary drivers of individual differences in learning gains are student characteristics, such as motivation and socioeconomic background, but especially intelligence, which explains between 50% and 80% of the variance within that student-attributed portion. These findings indicate that although high-quality teaching can improve the classroom environment, its overall impact on student performance dwarfs that of underlying cognitive and personal attributes, particularly in affluent, developed settings.

The main message of the referenced study10 that articulated these findings was: “as long as educational research fails to focus on students’ characteristics, we will never understand education or be able to improve it.” There may no better example of ignoring this warning than the $575 million effort funded from the Gates Foundation ($212 million) and school districts ($363 million) to improve student achievement by increasing teacher effectiveness. It failed for both individuals and for increasing group averages11. However, of course, students can learn many relevant things in school without changing their intelligence levels; brighter students will still show greater learning outcomes, but not-so-bright students will now have more knowledge and skills than what was observed before the educational intervention.

Ultimately, a key value judgement can be derived from the data reviewed so far. It is well summed-up in a quote from the article “Overstating the Role of Environmental Factors in Success: A Cautionary Note”12: “recognizing and understanding individual differences, rather than denying or undermining their importance, leads to politics of equity – providing individuals with the means to thrive – rather than equality – treating everyone uniformly regardless of their specific needs.” (2019, p. 4)

Key points

- While some preschool programs have shown long-term results for some important outcomes, increasing intelligence is not one of them. Some intensive programs may help some aspects of cognitive development for the most disadvantaged students, but large-scale projects have not yet been done.

- It is probably unrealistic to expect long-lasting effects from limited interventions.

- Education has some impact on intelligence into adulthood (possibly between 1 and 5 IQ points), but not as much as we might think. However, there is no compelling evidence that education increases the g-factor.

- Athough high-quality teaching can improve the classroom environment, its overall impact on student performance dwarfs that of underlying cognitive and personal attributes, particularly in affluent, developed settings.

Arthur Jensen (1981, p. 241)13:

The student who wants to play basketball doesn’t think about trying to increase his height, but works at developing the specific skills that will improve his actual performance in basketball, and by so doing he will become a better player. The very few who become champions will have done much the same, and, in addition, will have exceptional physical advantages (including being very tall) for which they (or their parents) should take no personal credit.

Change height to g and the point is clear.

References

Footnotes

-

https://arthurjensen.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/How-Much-Can-We-Boost-IQ-and-Scholastic-Achievement-OCR.pdf ↩ ↩2

-

Johnson, W. 2012. How much can we boost IQ? An updated look at Jensen’s (1969) question and answer. In Slater, A., & Quinn, P. (eds.), Developmental psychology: Revisiting the classic studies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016028961500135X ↩ ↩2

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016028961630068X ↩

-

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329055215_Overstating_the_Role_of_Environmental_Factors_in_Success_A_Cautionary_Note ↩

-

https://arthurjensen.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Straight-Talk-About-Mental-Tests-Arthur-R.-Jensen.pdf ↩