- The stability of g across the entire life span is high, surpassing that of any single psychological trait.

- Fluid reasoning decreases over the adult life span, while crystallized abilities remain stable or even increase slightly until people are in the retirement years.

- For reaction time and the functioning of the working memory system, the degree of decrease accelerates after the mid-sixties.

- By late childhood, the genetic contribution to the stability of intelligence was 75 percent, whereas nonshared environment (largely randomness) contributes 20 percent.

Introduction

Like height, intelligence increases in the first years of life, remains at similar values for decades, and then declines at old age. Those taller in childhood tend to be the tallest in old age. This same pattern is found for intelligence test scores. In a longitudinal study1, 262 men at age eighteen were examined and reassessed at age fifty, and then again at five-year intervals up to age sixty-five. Three intelligence measures were administered at age eighteen, four intelligence measures were administered at age fifty, and subsequently, working memory capacity was assessed with two other tasks. The data were analyzed with a refined statistical method for comparing latent variables (MGCFA—Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis). The measurement of the latent g-factor (at ages eighteen, fifty, fifty-five, sixty, and sixty-five) was stable over the nearly fifty-year period of study, consistent with observations of other longitudinal studies, even though different tests were used. The key findings based on the latent g-factor were that (1) the stability of g was high (0.90) when variance specific to the administered tests was removed, (2) the correlation between g assessed at age eighteen and working memory assessed fifty years later was substantial (0.60), and (3) the concurrent correlation between g and working memory (at age sixty-five) was high (0.90). There is no other psychological trait that shows the stability values we just enumerated.

Aging and intelligence are discussed in this article from three approaches: (1) psychometric, (2) information processing, and (3) biological. But first, how is the relationship between aging and intelligence studied? Understanding this is important for properly interpreting the various psychometric data.

Research Designs

Three basic research designs have been used in the study of aging. The simplest is the cross-sectional design (CSD), where the scientist takes measurements on people in different age groups, at roughly the same time. The positive aspects of CSDs are that they are relatively easy to conduct compared to other alternatives, and they provide a picture of differences in the intellectual abilities of different age groups (cohorts) in the population, as exists at the time of testing. However, CSDs pose problems of interpretation. It is difficult to obtain samples in which the participants differ only in age. For instance, elderly participants (seventy and over) will report having had fewer years of education, on average, than younger adults. This reflects changes in society, rather than psychological changes in the individuals, but it produces an unavoidable confound between any age and education effects. The general principle is that in cross-sectional designs, age effects are confounded with cohort effects, leaving researchers unable to determine the effect that causes differences between groups. Additionally, because cross-sectional studies measure each individual only once, there is no way to distinguish between gradual and sudden changes in cognitive ability.

In a longitudinal design, the same people are studied across several time intervals. Therefore, instead of studying age differences, age-related changes are studied. The contrast between cross-sectional and longitudinal results is informative. Intelligence test scores show considerably less drop over the adult years in longitudinal studies than they do in cross-sectional studies. This is in part due to the confounding of age and cohort effects in the cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies are expensive and time-consuming. They are also prone to the recruitment/attrition effects, because people with lower test scores at baseline are more likely to decline participation or to quit the study than people with high test scores. Thus, unless allowance is made for nonrandom attrition effects, aging may appear to be less debilitating than it actually is.

The gold standard is the cohort-sequential design, like the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS; Schaie, 2013)2. In this design, scientists recruit people of different ages at the start, follow them as in a longitudinal study, and in addition, periodically recruit new participants and follow them as well. This allows for a separate evaluation of cohort (age differences) and aging (age changes) effects and provides for longitudinal studies of different cohorts.

Psychometrics

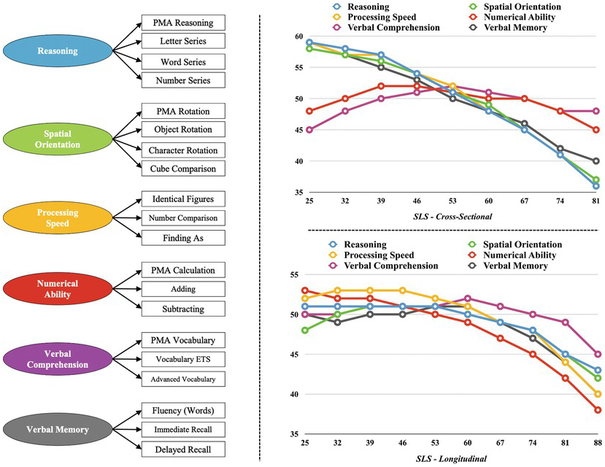

The figure below2 shows the cognitive abilities measured in the Seattle Longitudinal Study2, along with the findings obtained in the cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons for reasoning, spatial orientation, processing speed, numerical ability, verbal comprehension, and verbal memory. Cross-sectional results show a decline in reasoning, spatial orientation, and processing speed at age forty-six. Verbal memory begins to show decline at age thirty-nine. Numerical ability and verbal comprehension show a smoother developmental pattern. The average difference between the youngest and the oldest cohorts is equivalent to 2 standard deviations. Longitudinal results reveal a significant decline in processing speed and numerical ability at age sixty. Reasoning, spatial orientation, and verbal memory decline at age sixty-seven. Verbal comprehension shows a significant decline at age eighty-one.

Combining cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, results showed that between twenty-five and eighty-eight years of age, (1) verbal comprehension declines 0.4 standard deviations, (2) reasoning and spatial orientation decline 0.8 standard deviations, (3) verbal memory declines 1.1 standard deviations, (4) processing speed declines 1.2 standard deviations, and (5) numerical ability declines 1.5 standard deviations. Therefore, the downward trend with increased age ranges between less than half a standard deviation for verbal comprehension to one and a half standard deviations for numerical ability.

Studies consistently show3 that Gc measures are more resistant to the aging process than measures of inductive reasoning (Gf). However, the studies are not consistent about precisely when the declines occur. In the SLS, some participants have dropped out over time, so there is a bias toward continued participation by people with higher initial cognitive abilities. This would result in an understatement of the age effect. Other studies indicate3 declines starting in the mid-twenties for Gf and in the mid-thirties for Gc, but these studies tend to be confounded with cohort effects (largely the Flynn Effect), which would lead to an overestimation of the deleterious effects of aging.

Dedifferentiation Hypothesis

There is also debate about the extent to which the pervasiveness of the general intelligence factor (g) increases with advanced age. Technically, this is called the dedifferentiation hypothesis. The hypothesis predicts that the correlations between measures of different types of intelligence, such as verbal and visuospatial reasoning, will increase with age. Good arguments can be advanced for this hypothesis. Declines in intelligence are usually associated with declines in health. Injuries that influence the brain should have widespread deleterious effects on cognitive performance, although their differential impact may change dramatically for different premorbid intelligence levels. Nonpathological reductions in the prefrontal cortex and other areas associated with the working memory system, which are typical of aging, are associated with lower fluid intelligence scores. Reduction in the capabilities of the working memory system should have a pervasive effect on almost all cognitive functions, which should lead to an increased influence of individual differences in g on performance. Nevertheless, the cognitive training literature fails to substantiate this presumption, because improvements in the working memory system fail to impact g (Protzko, 2017)4.

The evidence for the dedifferentiation hypothesis is mixed5. However, a comprehensive meta-analysis comes to a robust conclusion: a general factor of cognitive aging (g-aging) strengthens with advancing adult age (Tucker-Drob et al., 2019)6. Their key research question was whether individual differences in longitudinal changes are related across different cognitive abilities. These were the main conclusions from the meta-analysis:

- Longitudinal individual differences in changes of distinguishable intellectual abilities are strongly correlated among themselves. If inductive reasoning decreases, for example, the remaining abilities also tend to decrease. Changes are coupled.

- The amount of variance in cognitive ability levels explained by the g was 56 percent, closely similar to the amount of shared variance in rates of change, which was 60 percent.

- Cognitive decline may operate along a similar general dimension as does cognitive development in general.

These findings were interpreted within the conceptual framework proposed by Manuel Juan-Espinosa and colleagues (2002)7, which they call the in-differentiation hypothesis: the structure of life-span changes in cognitive abilities may be invariant in much the same way that the structure of changes in human anatomy are invariant. They proposed an anatomical metaphor:

As the human skeleton, there is a basic structure of intelligence that is present early in life. This basic structure does not change at all, although, like the human bones, the cognitive abilities grow up and decline at different periods of life” (p. 406).

Information Processing

Information processes are essentially hypothetical constructs used by cognitive theorists to describe how individuals apprehend, discriminate, select, and attend to specific aspects of the vast array of stimuli they receive. Working memory is an example of an information-processing concept, in the sense that it refers to an abstract ability to manipulate and/or hold pieces of information in the mind, without specifying what these pieces of information mean in the world.

Executive Function and Working Memory

The age-related breakdown in the working memory system is shown by decreased performance in short-term memory span tasks, greater susceptibility to interruption or distraction, and poorer control on dual tasks, such as simultaneously monitoring a stream of visual and auditory signals. These measures are, in general, those that are most closely related to psychometric measures of g and Gf. On one hand, the failure in working memory functioning appears to be general, rather than associated with a particular component of the working memory system. On the other hand, executive updating of information in short-term memory may play an important role.

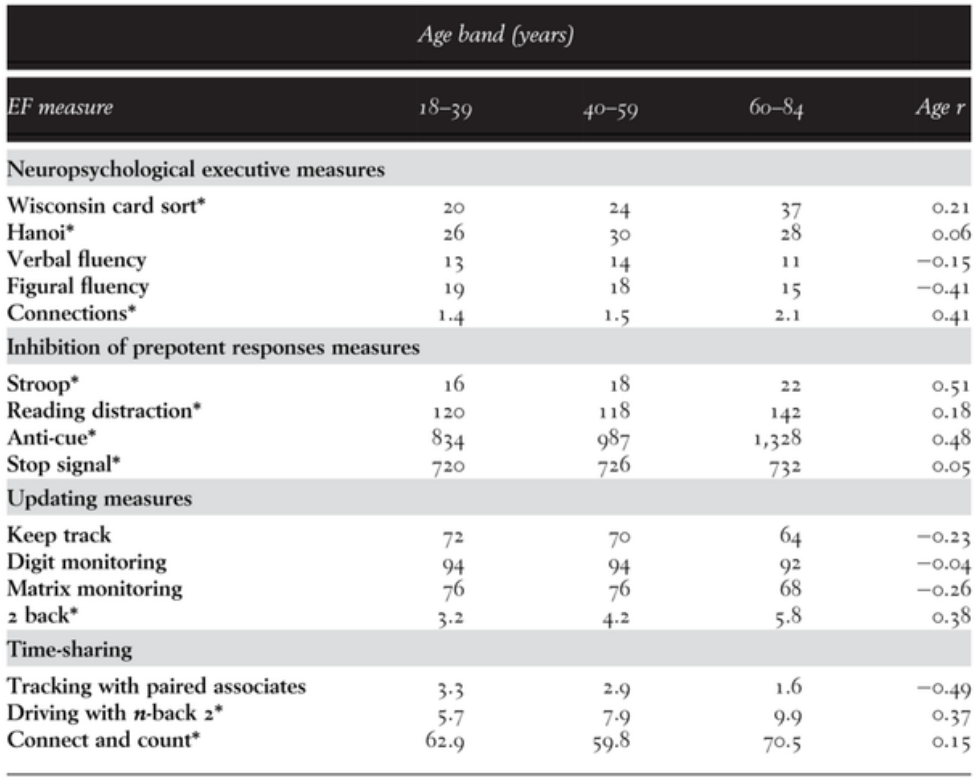

Timothy Salthouse and colleagues (2003)8 asked if executive function may account for age-related intellectual decline. Is this decline attenuated when individual differences in executive functioning are controlled? To answer this question, data were obtained from 261 adults (age range eighteen to eighty-four) who completed a comprehensive battery of tests. Average performance scores across age bands for executive functioning (EF) measures are listed in the table below.

The findings from this comprehensive study led to four main conclusions:

- The executive function, updating, and time-sharing constructs showed very high correlations (r > 0.85) with fluid reasoning (Gf). Therefore, they might be tapping shared cognitive processes. The implication is that it does not make sense to control for executive functioning differences and see if this attenuates intellectual decline. Recall that diminished cognitive performances across age are coupled6.

- The specifics of executive functioning are much less important than usually assumed within the neuropsychological literature. Typical executive functioning measures tap cognitive processes shared by standardized measures of intelligence.

- The updating construct is more closely related to fluid reasoning (r = 0.93) than to memory (r = 0.72), speed (r = 0.79), and vocabulary (r = 0.30). This might support a distributed network involved in fluid intelligence and executive control in the brain.

- The executive function measures usually administered in neuropsychological research may not qualify as distinguishable psychological constructs beyond the classic standardized measures of intelligence: “one needs to be cautious in postulating the existence of a new construct without relevant empirical evidence that it is distinct from constructs that have already been identified” (Salthouse et al., 2003, p. 589)8.

Unfortunately, this last point is a recurrent problem in psychological research generally. Using a new label, such as executive functioning (EF), for designating a set of tasks does not prove that we are tapping different cognitive processes than those available measures, like intelligence tests, do not tap. Discriminant validity must be demonstrated before accepting the supposed new construct. At this construct level, the general factor of intelligence (g) and EF are almost identical with respect to the pattern of individual differences. This observation is corroborated in lesion mapping studies of intelligence and executive function (Barbey et al., 2012)9.

Mental Chronometry

Information processing occurs in real time, with each step in the process taking a certain amount of time. Time itself, therefore, is the natural scale of measurement for the study of information processes and the individual differences therein, hence the field of mental chronometry. Because time is measured on an absolute, or ratio, scale with international standard units, it has certain theoretical and scientific advantages over ordinary test scores. Test scores are based on the number of items answered correctly on a particular test and, therefore, must be interpreted in relation to the corresponding performance in some defined “normative” population or reference group.

Many studies show cognitive slowing trends, but one of the most sound was conducted by Geoff Der and Ian Deary (2006)10. They surveyed a large sample of the UK population (N = 7,414), finding marked slowing of simple (SRT) and choice (CRT) reaction times with age. Choice reaction time, which requires more complex decisions, was more sensitive to aging. Reaction times slow, and results also become more variable with aging. These were their three main conclusions: (1) SRT fails to show any increase until age fifty (longer RT is a slower time); (2) CRT increases across the whole life span, and the values become more variable with age; and (3) the correlation between SRT and CRT was 0.67. The correlation between general intelligence (g) and SRT was r = −0.31, whereas the correlation between CRT and g was r = −0.49 (Der and Deary, 2003)11. The higher g is, the faster are the SRT and CRT values (i.e., greater processing speed, especially for CRT).

Intrasubject deviation (ISD) is measured as the standard deviation of an individual's RTs across trials. ISD can be thought of as essentially “inconsistency”. Interestingly, ISD is often more highly correlated with intelligence than the mean and median RT. ISD increasing with age has been viewed as a manifestation of "neural noise" or a decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio of neural transmissions.

The late Arthur Jensen (author of The g Factor: The Science of Mental Ability) described cognitive aging as a unitary "global slowing" of the central nervous system12. Using Brinley plots (scatter plots used to compare speed between groups), Jensen demonstrates that the mean RTs of older adults across various tasks can be predicted by multiplying the mean RTs of younger adults by a constant factor. This implies that aging does not typically affect specific, isolated cognitive processes, but rather represents a global reduction in the "cycle time" of the brain's information processing. In theory, this slowing has a cascade effect: as processing speed declines, the capacity of working memory is reduced because information decays before the necessary mental operations can be completed, which then impacts Gf, since fluid reasoning depends upon the working memory system. In Jensen's view, the brain can be likened to a central processing unit (CPU) in a computer. The clock speed of that CPU determines how quickly it can execute instructions. In childhood, the hardware is "upgrading" as the wires become better insulated (myelination), allowing the system to run faster and handle more complex software. In aging, the system experiences a global reduction in clock speed; it is not that the software (knowledge) is deleted, but that the processor takes longer to execute every command, eventually reaching a point where complex programs "time out" because the hardware can no longer keep up with the demands. Jensen spells out the relationship between RT and intelligence (g) in his 2006 book titled Clocking the mind: Mental Chronometry and Individual Differences12, speculating it to reflect the speed and efficiency of information processing in the central nervous system.

Biology

Individual differences in mental test scores have a substantial genetic component, as indexed by the coefficient of heritability (in the broad sense), which is the proportion of the population variance in test scores attributable to all sources of genetic variability. On the other hand, environmental variance can be partitioned into two sources: (1) environmental influences that are shared among children reared in the same family but that differ between families, and (2) nonshared environmental influences that are specific to each child in the same family and therefore differ within families.

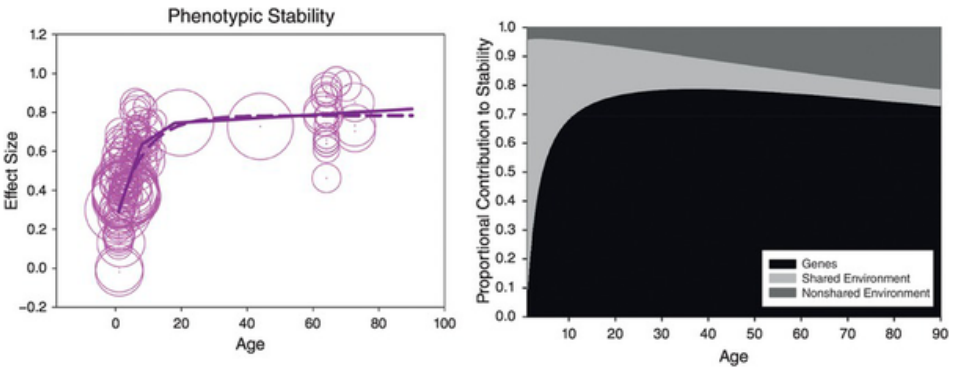

Elliot Tucker-Drob and Daniel Briley (2014)13 analyzed the issue of the genetic and nongenetic contributions to intelligence differences across the life span. They conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of longitudinal twin and adoption studies. It included 150 combinations of time points and measures from fifteen longitudinal samples (4,548 MZT pairs, 7,777 DZT pairs, 34 MZ adopted pairs, 78 DZ adopted pairs, 141 adoptive sibling pairs, and 143 nonadoptive sibling pairs). The age range was from six months to seventy-seven years. Results showed that the stability of intelligence increases from effect sizes of 0.30 in early life to 0.6 at age ten and 0.7 at age sixteen, then reaches an asymptote (0.78) (left of figure). These were the main findings regarding the contribution of genetic and nongenetic factors to stability:

- While the contribution of genetic factors is null in early life, their relevance increases through child development and stabilizes at an asymptote effect size of 0.65 in adulthood. The increase in heritability of IQ with age is a finding known as the Wilson effect.

- Shared environment contributes moderately to stability in childhood (effect size 0.24), and this contribution fades to zero values by middle adulthood.

- Nonshared environment makes a very small contribution, although it increases somewhat with advanced age.

- By late childhood, the genetic contribution to the stability of intelligence was 75 percent, whereas nonshared environment contributes 20 percent.

The authors argue that these results support transactional models of cognitive development, underscoring gene–environment correlation and interaction. If shared environmental influences accumulate their influence on cognition over time through variables like social class or school quality, depending on children’s genotypes, then the estimates of the contribution of shared environment to stability should decrease with increased age, and this is what was found. Furthermore, the gene–environment correlation should lead to increases with age in the genetic contribution to stability, and this too was supported in the meta-analysis:

As children increasingly select and evoke differential levels of stimulation on the basis of their genotypes over time, genetic stability will increase. These considerations together indicate that estimates of genetic influence are likely to reflect environmentally mediated mechanisms” (p. 971)13.

The specific sources of much of the nonshared (within-family) environmental variance are still not entirely identified, but a large part of the specific environmental variance appears to be due to the additive effects of a large number of more or less random and largely physical events—developmental “noise”— with small, but variable positive and negative influences on the neurophysiological substrate of mental growth.

References

Rönnlund, M., Sundström, A., Nilsson, L.-G., & Nyberg, L. (2015). Interindividual differences in general cognitive ability from age 18 to age 65 years are extremely stable and strongly associated with working memory capacity. Intelligence, 53, 59–64. https://gwern.net/doc/iq/2015-ronnlund.pdf ↩︎

Schaie, K. W., & Willis, S. L. (2010). The Seattle Longitudinal Study of Adult Cognitive Development. ISSBD bulletin, 57(1), 24–29. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3607395/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

McArdle, J. J., Ferrer-Caja, E., Hamagami, F., & Woodcock, R. W. (2002). Comparative longitudinal structural analyses of the growth and decline of multiple intellectual abilities over the life span. Developmental psychology, 38(1), 115–142. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11806695/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Protzko J. (2017). Effects of cognitive training on the structure of intelligence. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 24(4), 1022–1031. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27844294/ ↩︎

de Frias, C. M., Lövdén, M., Lindenberger, U., & Nilsson, L.-G. (2007). Revisiting the dedifferentiation hypothesis with longitudinal multi-cohort data. Intelligence, 35(4), 381–392. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0160289606001188 ↩︎

Tucker-Drob E. M. (2019). Cognitive Aging and Dementia: A Life Span Perspective. Annual review of developmental psychology, 1, 177–196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34046638/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Juan-Espinosa, M., García, L. F., Escorial, S., & Rebollo, I. (2002). Age dedifferentiation hypothesis: Evidence from the WAIS-III. Intelligence, 30(5), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(02)00092-2 ↩︎

Salthouse, T. A., Atkinson, T. M., & Berish, D. E. 2003. Executive functioning as a potential mediator of age-related cognitive decline in normal adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132, 566–594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14640849/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Barbey, A. K., Colom, R., Solomon, J., et al. 2012. An integrative architecture for general intelligence and executive function revealed by lesion mapping. Brain, 135, 1154–1164. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22396393/ ↩︎

Der, G., & Deary, I. J. (2006). Age and sex differences in reaction time in adulthood: results from the United Kingdom Health and Lifestyle Survey. Psychology and aging, 21(1), 62–73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16594792/ ↩︎

Der, G., & Deary, I. J. (2003). IQ, reaction time and the differentiation hypothesis. Intelligence, 31(5), 491–503. https://gwern.net/doc/iq/2003-der.pdf ↩︎

Jensen, A. R. (2006). Clocking the mind: Mental chronometry and individual differences. Elsevier. https://arthurjensen.net/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Tucker-Drob, E. M., & Briley, D. A. (2014). Continuity of genetic and environmental influences on cognition across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal twin and adoption studies. Psychological bulletin, 140(4), 949–979. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4069230/ ↩︎ ↩︎