Who was Richard Feynman?

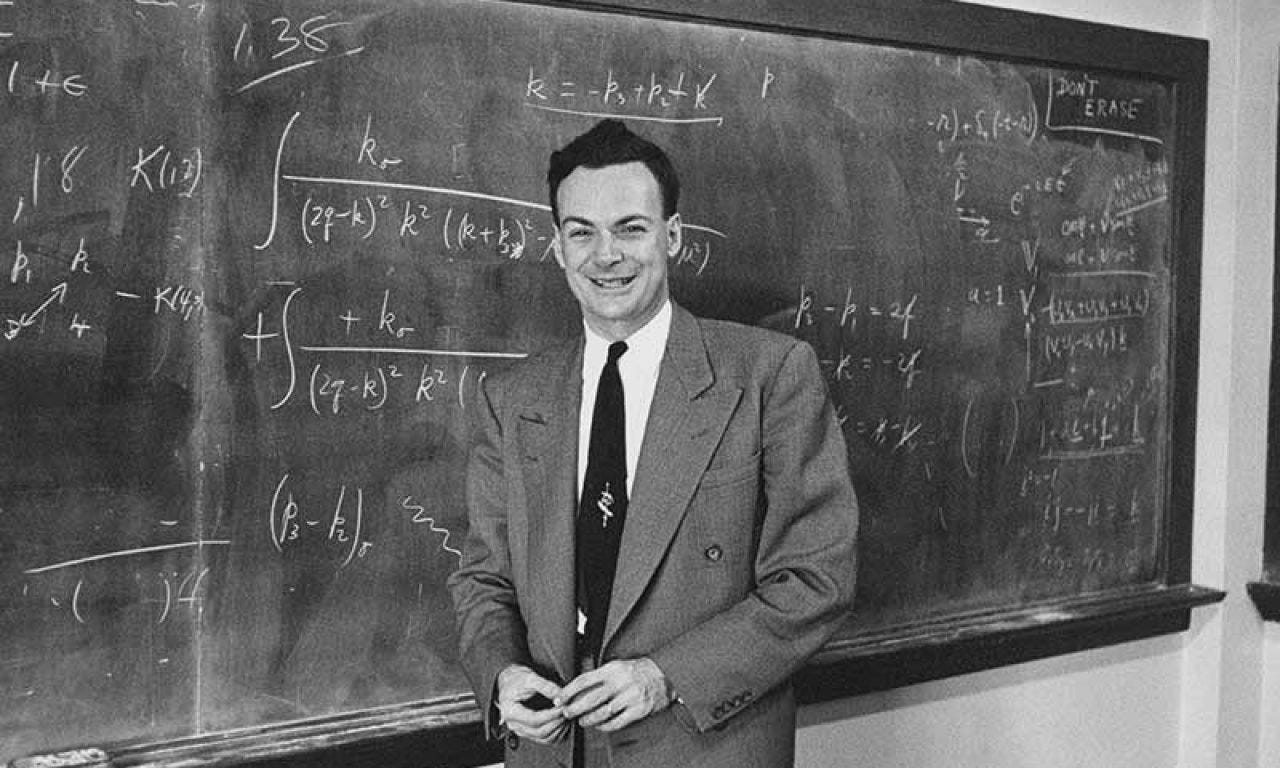

Richard Feynman was a theoretical physicist whose work left a enduring impact on modern physics. He made major contributions to quantum electrodynamics, developed the diagrammatic methods (now known as Feynman diagrams), and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 for his major contributions to the field. During World War II, he also participated in the Manhattan Project, the research program which produced the first nuclear weapons.

Because of Feynman's intellectual achievements and reputation for exceptional reasoning ability, he is often referenced in discussions about intelligence and IQ, making him a recurring figure in debates over what such IQ scores actually measure.

What was Richard Feynman's IQ?

A common claim is that the physicist Richard Feynman had an IQ of 125. This number is often cited as evidence that IQ tests are unreliable or that extraordinary intellectual achievement does not require exceptional intelligence (as Feynman was able to achieve so much with "only" an IQ of 125). However, a closer look at the score shows that such conclusions are based on incomplete and misleading information.

The IQ score of 125 attributed to Feynman comes from a test he reportedly took as an adolescent while still in high school. Because of this, the score is unlikely to reflect his full cognitive capabilities as an adult. Intelligence, particularly higher-level reasoning ability, continues to develop through late adolescence and early adulthood, meaning test scores from childhood should not be treated as definitive measures of adulthood IQ.

How do IQ tests work and what is the difference between a Full-Scale IQ and a Verbal IQ score?

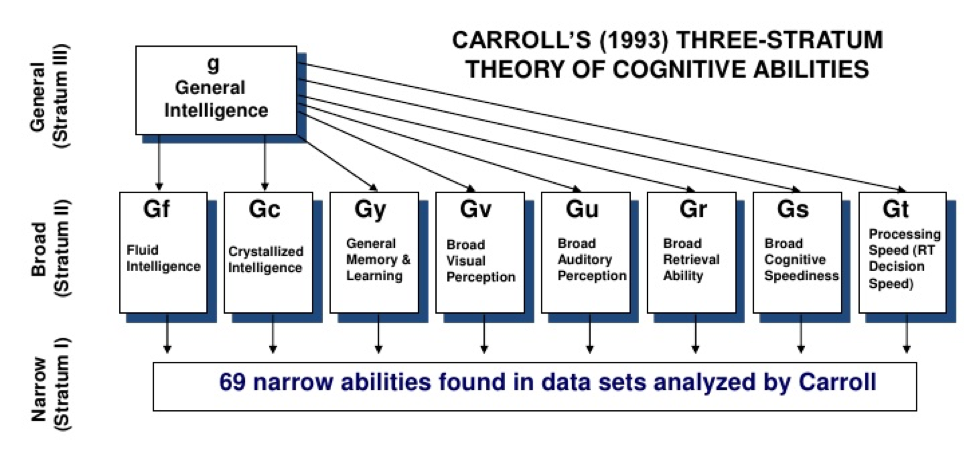

Deviation IQ tests are designed to measure a broad range of cognitive abilities rather than a single trait. Most modern tests are based on hierarchical models of intelligence, such as the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) framework, which models intelligence (g) as a combination of general ability and multiple more specific cognitive skills.

Under this approach, the shared variance between many diverse cognitive tasks can be summarized using a Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ) score. The most common types of tasks include verbal comprehension, fluid reasoning, quantitative ability, working memory, and processing speed. By aggregating performance across these areas, FSIQ provides the most comprehensive single estimate of general cognitive ability.

By contrast, a Verbal IQ score reflects performance on tasks that primarily measure crystallized knowledge, such as vocabulary knowledge, reading comprehension, and verbal reasoning. While verbal ability is an important component of intelligence, it represents only one subset of cognitive functioning. By only measuring verbal tests, a strong performance in nonverbal or abstract reasoning domains may not be captured by verbal measures alone. Most people show uneven patterns of ability, performing strongly in some cognitive areas while showing relative weaknesses in others.

Limitations of the Test Itself

There is also no clear information about the nature of the test Feynman took. Taking into account common scholastic aptitude tests administered at the time, it is widely speculated that the exam was measuring verbal IQ rather than full-scale IQ. If so, this would have neglected areas in which Feynman was especially strong, such as abstract reasoning, quantitative knowledge, and fluid problem-solving ability.

Without knowing whether the test measured full-scale IQ (FSIQ) or was limited to a narrow subset of abilities, the resulting score cannot be treated as a comprehensive assessment of his intelligence.

According to his biographer, in high school the brilliant mathematician Richard Feynman's score on the school's IQ test was a 'merely respectable 125' (Gleick, 1992, p. 30). It was probably a paper-and-pencil test that had a ceiling, and an IQ of 125 under these circumstances is hardly to be shrugged off, because it is about 1.6 standard deviations above the mean of 100. The general experience of psychologists in applying tests would lead them to expect that Feynman would have made a much higher IQ if he had been properly tested.

John Carroll, The Nature of Mathematical Thinking, p. 9

Why 125 Is Not a “Low” Verbal Score

Even taken at face value, an IQ score of 125 is far from average. It corresponds to approximately 1.6 standard deviations above the mean, placing an individual well into the top few percent of the population. Under the testing conditions described, such a score would already indicate unusually high cognitive ability.

More importantly, psychologists familiar with intelligence testing consistently note that ceiling effects and limited test formats often underestimate the abilities of exceptionally gifted individuals. In other words, the test may simply not have been capable of capturing Feynman’s true intellectual range.

Why the Feynman IQ Claim Is Often Misused

The “Feynman had an IQ of 125” claim is frequently presented as an outlier intended to undermine the validity of IQ testing altogether. However, this argument ignores critical context: the age at which the test was taken, the unknown structure of the exam, and the likelihood that it failed to measure full-scale intelligence.

Because of these limitations, no qualified psychologist would consider this score to be a representative or definitive measure of Feynman’s intellectual ability. At best, it reflects a partial snapshot taken under constrained conditions; at worst, it is a misleading data point used far beyond its legitimate scope.

What Can We Actually Conclude?

Feynman’s true IQ, if measured properly in adulthood using a modern, high-ceiling test, was almost certainly higher than 125. How much higher is impossible to determine due to the lack of reliable data. What can be said with confidence is that the commonly referenced score does not accurately capture the cognitive profile of one of the most intellectually gifted physicists of the twentieth century.

Comments

Sign in to leave a comment.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!